We are one week away from the 2024 total solar eclipse. So, get out your smoked glass and let’s explore a few burning questions about this cosmic phenomenon!

What makes the eclipse on April 8, 2024, a “once-in-a-lifetime” event?

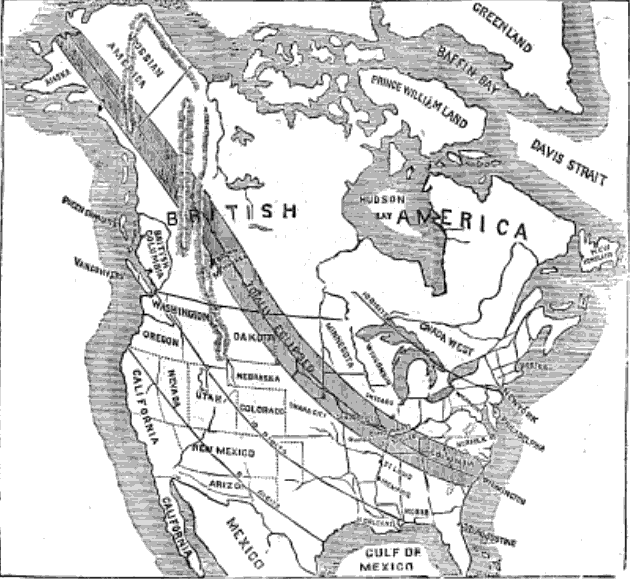

Every year, there are at least two solar eclipses and about every eighteen months, there is a total solar eclipse somewhere in the world. According to NASA, “it will take about a thousand years for every geographic location in the lower 48 states to be able to view a total solar eclipse” and scientists note these eclipses “recur only once every 360 to 410 years, on average, at any given place.”1 Based on these estimates, the next solar eclipse to travel across the continental United States from coast to coast will be in 2045 and the next total solar eclipse with visibility in Ohio won’t happen until 2099. Of course, these are averages and estimates used to predict the future (and astronomers have gotten quite good at that!), but if we look to the past, we can see just how rare next week’s eclipse is for Mansfield and Ohio.

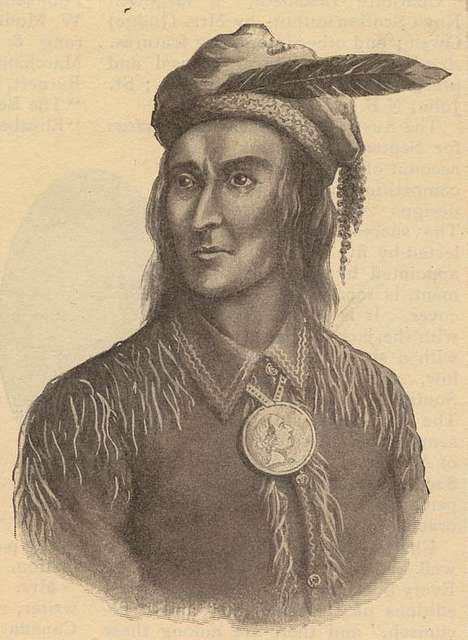

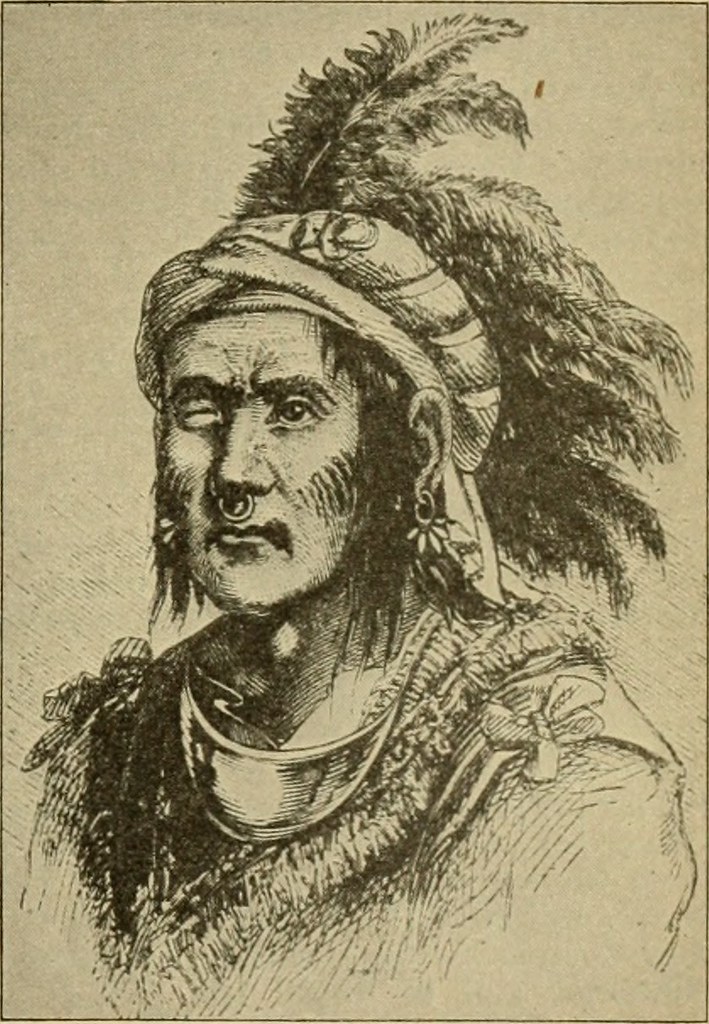

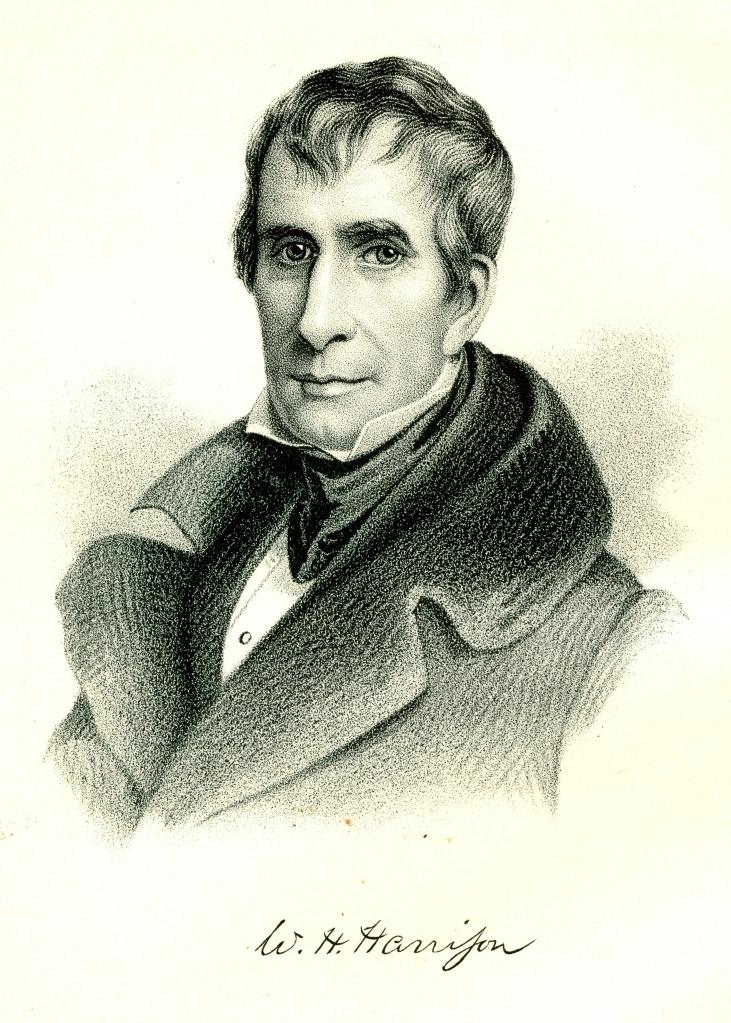

The last time a total solar eclipse was visible in Ohio was on June 16, 1806. Mansfield, established as a city in 1808, didn’t exist yet and Ohio’s statehood was only three years old. Also known as “Tecumseh’s Eclipse, the 1806 event marked a significant moment in settler and Native American relations on the frontier.2 The prevailing legend is that, with a fraught peace treaty governing the northwest corner of Ohio (the Greenville Treaty) and a group of Native Americans fighting that treaty agreement in the Indiana Territory, General William Henry Harrison took a direct challenge to Shawnee leaders Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa. Tecumseh and his brothers were very influential figures in this area. Tenskwatawa, a Shawnee prophet, had “hundreds of devotees who followed his every word.”3 Harrison, then governor of the Indiana Territory, challenged Tenskwatawa in a letter dated April 12, 1806, saying if Tenskwatawa could perform miracles, surely, he could “cause the sun to stand still, the moon to alter its course, the rivers to cease to flow or the dead to rise from the graves.”4 Harrison wanted to discredit the Shawnee leader but only embarrassed himself in the process. Several historical accounts assert that Tenskwatawa responded to Harrison’s challenge, proclaiming that “in exactly 50 days he would make the moon cover the sun and it would be dark as night.”5 We do not know exactly when Tenskwatawa delivered his response to Harrison or whether exactly fifty days had passed when the moon moved to block the sun just before noon on June 16, 1806 (Harrison’s letter was written sixty-five days before the eclipse). At this point, solar eclipses were nothing new to European and Asian scientists and observers, but there were almost thirty years between the first documented eclipse sighting in the United States and the 1806 event – the first eclipse observed in the infant country was on June 24, 1778, visible over modern-day Louisiana.6 Therefore, it is not a stretch to suggest that the 1806 eclipse was something settlers on the frontier had never seen before. Anyone, besides Harrison, who may have doubted Tenskwatawa’s prophetic authority were awestruck by the accuracy of his prediction. Those with connections outside the territory, however, may have been granted advance notice of the coming eclipse as announcements had been printed in newspapers in Kentucky, Virginia, Maryland, and elsewhere. In fact, author Paul Cozzens noted the coming of the eclipse was “common knowledge in Detroit where [Tecumseh’s] British allies camped.”7 Regardless how Tenskwatawa came to know about the eclipse (whether he used established scientific predictions to his advantage or not), Harrison, having failed in humiliating Tenskwatawa, only grew angrier and many believe the mutual animosity boiled over five years later in the 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe that ushered in the War of 1812.8

Another popular tale out of Medina County, Ohio, suggests it was a female member of the Wyandot tribe who predicted the 1806 eclipse. In May 1806, she told others in her tribe “that a great darkness would soon fall over the Earth.”9 Unlike the story of Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa, it was not the settler population that did not trust the native woman, but, rather, her own tribe that turned against her. The tribe members considered her prediction to be “a dire threat” and they accused her of practicing witchcraft.10 According to historian Charles Neil, a council of tribe leaders decided she “should suffer death by strangulation by having invoked the powers of the evil one.”11 Her fate was sealed a few weeks before the eclipse and some of the tribe members responsible for her death may have believed the eclipse was an act of dark revenge from the witch on the other side.12 This nameless woman’s story is far less common in Ohio eclipse lore likely because the details are sparse and she went to the gallows unidentified, but she is representative of the prevailing wisdom of the time. In nearby Summit County, it is reported that citizens observing the eclipse were “greatly frightened, notwithstanding the event had been foretold by some of the squaws who apparently had gotten knowledge from more enlightened white people. The squaws were not believed and were put to death for witchcraft.”13

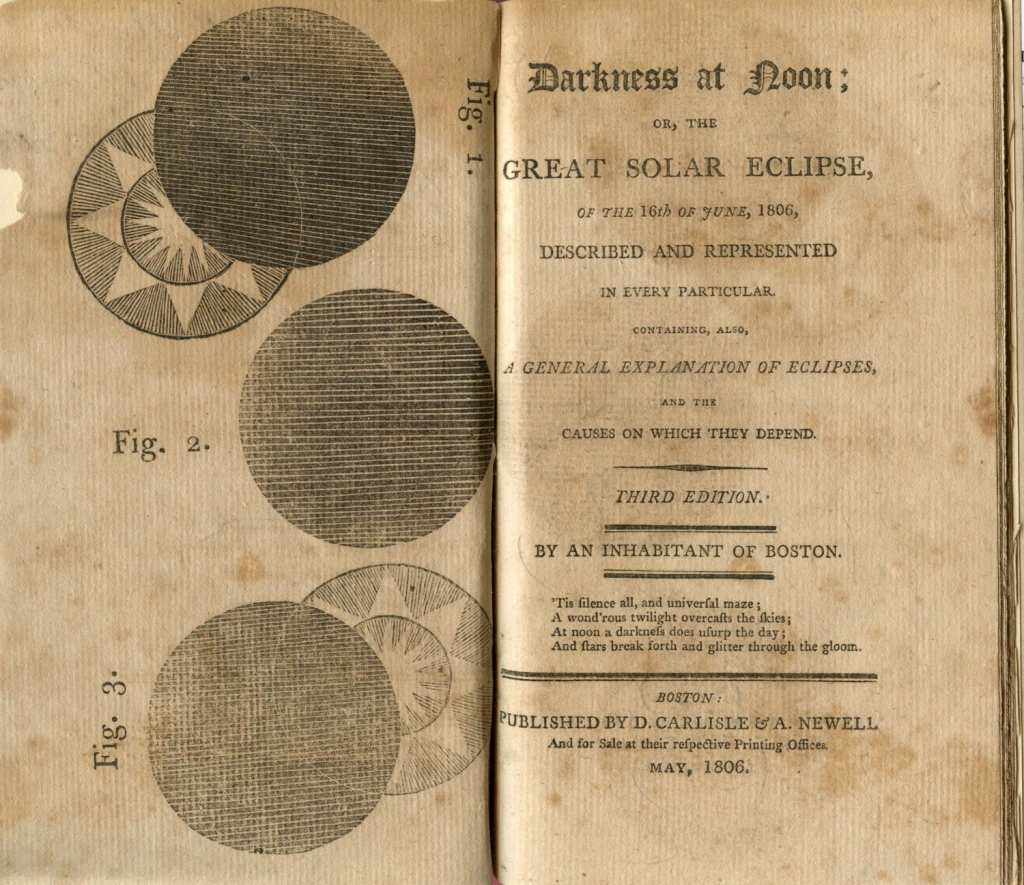

The 1806 eclipse was regarded by astronomers for over half a century as the most memorable one because it was seen “over all parts of North America.”14 As The Butler County Press of Hamilton, Ohio, reported in 1917, “the day was a remarkably fine one, scarcely a cloud being visible in any part of the heavens.”15 An incredible sight, surely, for those educated in such astronomical phenomena. Michael E. Bakich notes that “before 1801, eclipse observations were largely descriptive in nature and primarily made to check to the mathematical calculations of astronomers.”16 By the middle of the nineteenth century, such observations relied less on written descriptions as they could now be visually represented in a more reliable way through photography. On July 28, 1851, Johan Julius Berkowski, a photographer at the Royal Observatory in Königsberg, Prussia, took the first successful photograph of an eclipse’s totality.17

In the 218 years since Ohio saw its last total solar eclipse, so much has changed! The brief moment of darkness that comes with the totality of the eclipse is now a marvel to behold instead of the harbinger of doom it was once thought to be.

Why do we wear special glasses to watch the eclipse?

In anticipation of a solar eclipse in August 1869, the Delaware Gazette in Delaware, Ohio, advised its readers, “in order to observe the eclipse a common opera-glass or small telescope of any kind, provided with a shade-glass to screen the eye will prove efficient. If nothing can be obtained, a bit of plain glass, smoked over a candle or lamp, in some parts more deeply shaded than in others, in order to suit the varying intensity of the sun’s rays, will give a good view of most of the phenomena.”18 Six decades after the notable eclipse of 1806, Ohioans were less inclined to believe the Earth had plunged into the darkness of night and now viewed solar eclipses with a healthy curiosity.

The negative effects of looking directly at the sun had long been recognized by scientists, philosophers, and the educated elite. According to Nick Thieme, Ibn al-Haytham, an Egyptian scientist in the tenth century, used the first pinhole camera to view an eclipse.19 This “camera” in its most basic form is a box with a small pinhole in one end and a translucent screen at the other. The light produced by the eclipse (or any other object) would go through the pinhole where it would be inverted and projected onto the translucent screen.20 Instead of looking directly at the eclipse, you would essentially be observing the eclipse’s shadow; better for your eyes but maybe not the most satisfying for the curious astronomer. King Louis XIV of France is credited with first utilizing smoked glass to view a full solar eclipse around 1706 – the smoked glass covering the lens of his telescope worked to dilute the harmful ultraviolet light of the sun.21 A 1798 encyclopedia published in Philadelphia notes, “the sun, tho’ [sic] to human eyes so extremely bright and splendid, is yet frequently observed, even through a telescope of but very small powers, to have dark spots on his surface. These were entirely unknown before the invention of telescopes, though they are sometimes of sufficient magnitude to be discerned by the naked eye, only looking through a smoked glass to prevent the brightness of the luminary from destroying the sight.”22 Smoked glass, in this instance, not only protected the observer’s eyes, it allowed them to see new markings on the sun and this is noted as the moment of discovery of solar spots.23 Throughout the nineteenth century, British and American newspapers understandably predicted high demand for smoked glass whenever an eclipse was on the horizon.

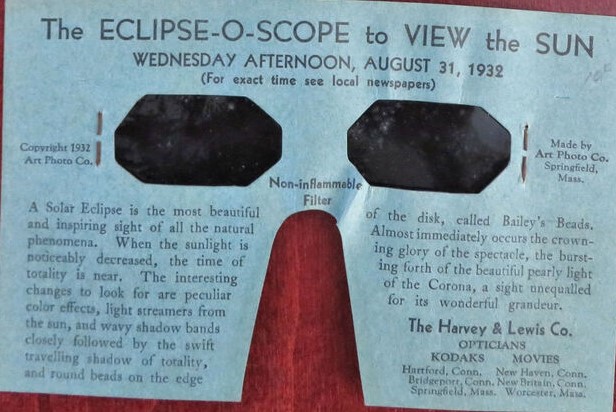

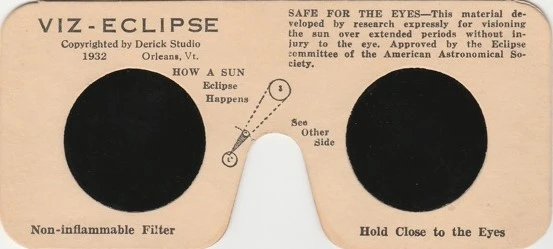

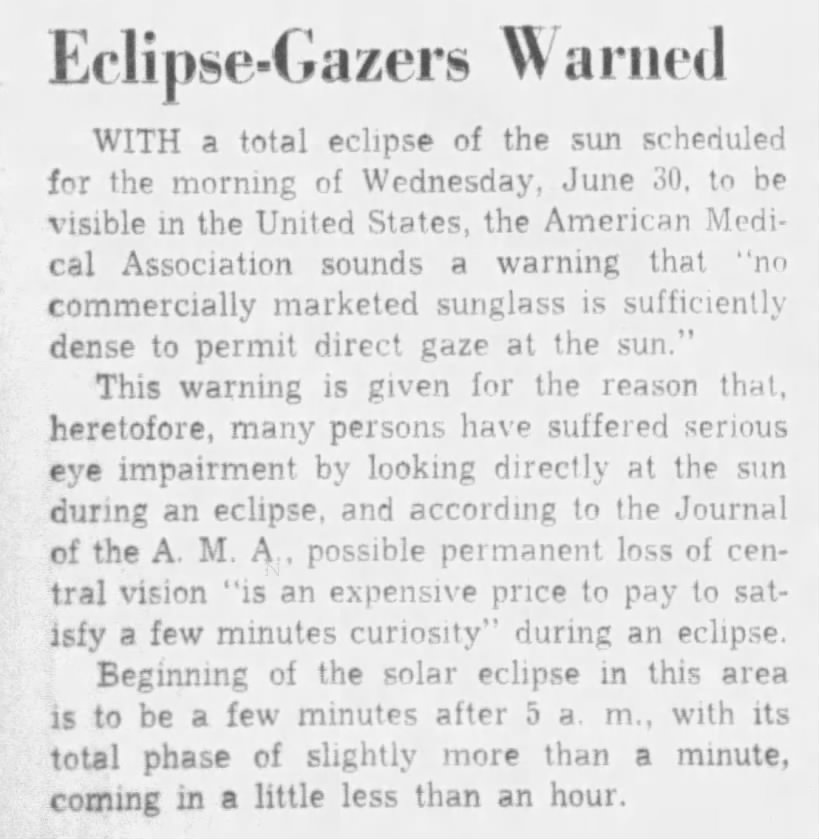

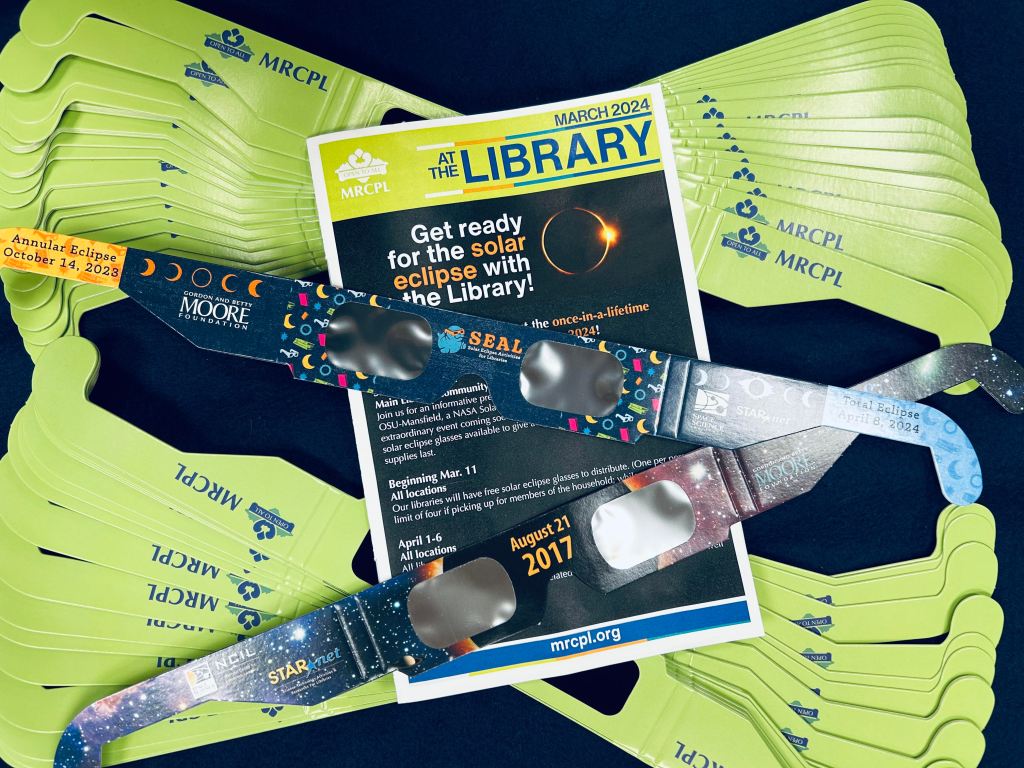

By the turn of the twentieth century, smoked glass was becoming less popular and new forms of eclipse eyewear emerged alongside new trends like 3D glasses. Harvey and Lewis, a New England optical supply company, and other similar ventures began producing Eclipse-o-Scope viewers in the 1930s. These were cardboard “eyeglasses” with a small sheet of protective film covering the eyeholes. A 1932 pair marketed as “Viz-Eclipse,” includes a note saying, “this material developed by research expressly for visioning the sun over extended periods without injury to the eye. Approved by Eclipse committee of the American Astronomical Society.”24 But, much like smoked glass and 3D glasses of the time, a user would have to the Eclipse-o-Scope or other viewer in front of their face and while eclipse totality is nowhere near as long as any popular 3D film, the protection offered by these early eclipse glasses was limited. In fact, by the end of World War II, at least one California physician determined smoked glass, photographic film, or even dark sunglasses are not enough protection from the sun.25 Still, others working in the fields of astronomy and physics believed as recently as 1974 that solar eclipses could be “viewed safely through a photographic negative or smoked glass.”26 Today, eclipse glasses are made from a resin containing carbon particles and are certified to meet standards approved by NASA. Contemporary eclipse glasses that you can get for free from the library before April 8, 2024, are made to “reduce the sun’s brightness by about 500,000 times;” regular sunglasses only reduce that brightness by a factor of five.27 Only time will tell if the science and fashion of eclipse eyewear have been perfected but the current sleek design that sits comfortably on your face has been in style since the 1970s.28 As long as the filters remain undamaged, eclipse glasses can be used indefinitely, but any small scratch or tear renders them unusable and it is suggested these glasses be discarded after three years.29

Does the Sherman Room have any eclipse materials in their collections?

Yes! We have a few pieces, including a 2020-2021 yearbook from Clear Fork High School with an eclipse theme. In the opening spread of the book, the editors talk about the Covid-19 pandemic and the atypical year it created, concluding that, like a solar eclipse, “even in the darkest of times, light remains.”30 Our collection also includes two pairs of eclipse glasses from the August 21, 2017, eclipse. Ohio was not in the path of totality for that eclipse, but these glasses commemorate what was dubbed “The Great American Solar Eclipse” since it was the first total solar eclipse visible from coast to coast in nearly a century. The News Journal also notes the 2017 eclipse was “the first total eclipse only visible in the United States since the nation’s founding.”31 Despite falling outside the path of totality in 2017, the Mansfield/Richland County Public Library still hosted programs to commemorate the event. Similarly, there has been an array of programs offered this year in anticipation of the April 8 eclipse. We have a copy of the March 2024 “At the Library” newsletter in our collection as well as three pairs of eclipse glasses marking both the April 8 total eclipse and an annular eclipse that took place on October 14, 2023.

Since the major history of eclipses in Ohio predates the library – and even Mansfield itself – there is an opportunity to begin preserving this history now. We encourage you to take photos (with all safety precautions in mind) or otherwise document your eclipse experience to share with your friends and family in the future. You are also welcome to donate your eclipse ephemera to the Sherman Room should you so desire, but please note that current collection policy guidelines still apply and we will not be accepting any more eclipse glasses. With seventy-five years until the next eclipse will be visible in Ohio and ninety-three until the next transit of Venus, this is our chance to document a once-in-a-lifetime event!

days

hours minutes seconds

until

Total Solar Eclipse

days

hours minutes seconds

until

Transit of Venus

- “Eclipses: Frequently Asked Questions,” NASA, https://science.nasa.gov/eclipses/faq/; Renee Stockdale-Homick, “Science Books and Films Presents a Read-Around-A-Theme on Solar Eclipses,” American Association for the Advancement of Science, https://www.aaas.org/resources/science-books-and-films-presents-read-around-theme-solar-eclipses. ↩︎

- Pam Cottrel, “The Total Solar Eclipse of 1806: How a Prediction from ‘The Prophet’ Shaped U.S.-Native American Relations, Springfield News-Sun, March 20, 2024, https://www.springfieldnewssun.com/local/the-total-solar-eclipse-of-1806-how-a-prediction-from-the-prophet-shaped-us-native-american-relations/G2W236VTUFB2TA6AZXUPQQEK6Y/. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Seth Borenstein, “Eclipse Lore Full of Blood, Sex, Even Some Snacking,” The Lima News [Lima, OH], August 20, 2017, 3; Sheridan Hendrix, “Fear, Awe and Tecumseh: What Was Life Like in Ohio During the 1806 Total Solar Eclipse,” The Columbus Dispatch, April 4, 2024, https://www.cincinnati.com/story/news/local/2024/04/04/how-tecumseh-used-the-1806-total-eclipse-in-ohio-to-his-advantage/72931327007/. ↩︎

- Cottrel, “The Total Solar Eclipse of 1806.” ↩︎

- Michael E. Bakich, “A History of Solar Eclipses,” Astronomy, April 5, 2023, https://www.astronomy.com/science/a-history-of-solar-eclipses/. ↩︎

- Cottrel, “The Total Solar Eclipse of 1806.” ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Mark J. Price, “Solar Eclipse Proved Deadly Prophesy for Indian Woman,” Akron Beacon Journal, June 6, 2016, B001 and B004. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Harry L. Hale, “True Tales about Ohio,” The Bluffton News [Bluffton, OH], November 20, 1958, 7. ↩︎

- “A Memorable Eclipse,” The Butler County Press [Hamilton, OH], January 5, 1917, 1. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Bakich, “A History of Solar Eclipses.” ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- “The Eclipse,” Delaware Gazette [Delaware, OH], August 6, 1869, 3. ↩︎

- Nick Thieme, “A Brief History of Eclipse Glasses and the People Who Forgot to Wear Them,” Slate, August 18, 2017, https://slate.com/technology/2017/08/a-history-of-eclipse-glasses-and-injuries.html. ↩︎

- Keith Gibbs, “The Pinhole Camera,” SchoolPhysics, 2020, https://www.schoolphysics.co.uk/age11-14/Light/text/Pinhole_camera/index.html; “Pinhole Camera,” March 15, 2021, https://scalar.chapman.edu/scalar/ah-331-history-of-photography-spring-2021-compendium/trinity-hall-essay-1. ↩︎

- Thieme, “A Brief History of Eclipse Glasses and the People Who Forgot to Wear Them.” ↩︎

- Thomas Dobson, Colin Macfarquhar, and George Gleig, Encyclopedia: Or, A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Miscellaneous Literature . . . and an Account of the Lives of the Most Eminent Persons in Every Nation, from the Earliest Ages Down to the Present Times (Philadelphia: Thomas Dobson at the Stone House, 1798): 433. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- “1932 Eclipse-O-Scope – Harvey and Lewis Opticians,” Vintage-Ephemera.com, https://vintage-ephemera.com/product-detail/389100157. ↩︎

- Thieme, “A Brief History of Eclipse Glasses and the People Who Forgot to Wear Them.” ↩︎

- “Eclipse Can Be Seen,” The Akron Beacon Journal, December 10, 1974, 18. ↩︎

- Thieme, “A Brief History of Eclipse Glasses and the People Who Forgot to Wear Them.” ↩︎

- Roger Sarkis, “History of Eclipse Glasses,” Eclipse Glasses USA, August 10, 2023, https://eclipse23.com/blogs/eclipse-education/history-of-eclipse-glasses. ↩︎

- Mindy Weisberger, “Will Your Eclipse Glasses Still Be Safe to Use in 2024,” LiveScience, August 25, 2017, https://www.livescience.com/60237-do-solar-eclipse-glasses-expire.html. ↩︎

- Clear Fork High School, Eclipse (Bellville, OH: 2021), 3, Sherman Room. ↩︎

- Courtney McNaull, “How to Safely View the Solar Eclipse,” News Journal, August 16, 2017, A1. ↩︎