One of the more prominent businesses to make its home in Mansfield was the Tappan Stove Company. But before the Tappan family found success under their own name, they were running the Eclipse Stove Company. This is not the story of that company, but, rather, the story that supposedly led to the inspired choice of Eclipse as the company’s name. Legend has it that after an 1889 fire destroyed their factory in Bellaire, Ohio, the decision was made to move the factory to Mansfield and rebrand with a nod to an astronomical phenomenon. In a 1966 News-Journal story, it is claimed that the Eclipse name was chosen to honor a late nineteenth century trip W.J. Tappan’s father, T.S., had taken to Siberia to photograph a solar eclipse.1 T.S. did indeed travel to Siberia but it was to photograph an eclipse of a different kind – the transit of Venus.

According to an 1869 piece in Scientific American Magazine, “a transit is nothing less than an eclipse of the sun by an inferior planet, the passage of either Venus or Mercury directly between the earth and the sun, so that their disks partially obscure its face, and appear as round, dark spots upon it. Conventional usage has limited the term eclipse of the sun to the obscuration of its disk by the moon, and transit to the same effect produced by the passage of Venus and Mercury between the earth and the sun, although there is no essential difference in the nature of the phenomena.”2 In reporting on the anticipated eclipses of the twentieth century, The Mansfield News wrote in November 1899, “The total solar eclipses visible in the United States will occur in 1918, 1923, 1925, 1945, 1954, 1979, 1984, and 1994. There will be 12 transits of Mercury, the first in 1907; but the more important transit of Venus will not occur, its next date being June 8, 2004.”3 While there are at least two solar eclipses every year, the transit of Venus is a very rare event, occurring four times every 243 years in a predictable and easy to remember patter of 105.5 years, 8 years, 121.5 years, 8 years.4 That essentially means when Venus does show her lovely face to the Earth, she will do it twice in fairly close succession before disappearing again for a long stretch of time. When T.S. Tappan was sent to Siberia in 1874 (and to New Mexico in 1882) as part of a government expedition to study the transit of Venus, his photographs would be some of both the first and last physical photographs of the event. Prior observations of the transit of Venus predated the invention of photography and subsequent instances came after the shift to digital photography, or, as astronomer William Harkness put it in 1882, “When the last transit season occurred the intellectual world was awakening from the slumber of ages, and that wondrous scientific activity which has led to our present advanced knowledge was just beginning.”5 Venus made its most recent trips across the sun in 2004 and 2012, but, sadly, the next event of this kind is not predicted to occur until December 21176 and, just as Harkness knew in 1882, “not even our children’s children will live to take part in the astronomy of that day”7 (for many of us, it’s not very likely will still be around in ninety-three years to see the next transit).

As the first nineteenth century transit of Venus approached, there was great excitement in the global scientific community. For centuries, since the first predicted transit in December 1631, one of the greatest unsolved problems in the history of astronomy had been “the accurate determination of the distance of the Sun from the Earth, and thus the scale of the solar system.”8 It was hoped that advancements in technology, particularly the addition of photography, would allow more accurate measurements to be collected and, thus, an answer to the great question of the universe – the scale of the solar system – could finally be determined. Russia, Great Britain, the United States, France, Germany, Italy, and Holland all organized scientific expeditions to document and study the 1874 transit, with one nineteenth century scholar commenting, “Every country which had a reputation to keep or gain for scientific zeal was forward to co-operate in the great cosmopolitan enterprise of the transit.”9 Despite the Russian government investing in twenty-six expedition teams of their own, the United States still insisted on sending a team of researchers to Siberia. There may have been one shared mission at the heart of each country’s expedition plan, but this was by no means a cooperative endeavor amongst the seven countries preparing for the transit.

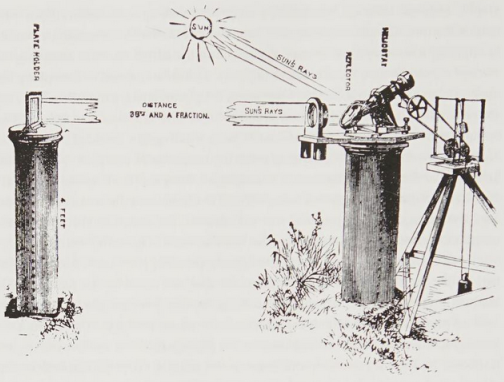

While the majority of the European countries with expedition teams devoted great attention to “securing the best photographs,” the American organizers sought to take measurements from the photographs themselves which would require a vastly different approach to setting up and working with the camera.10 Thus, the Americans set about equipping their teams with a fixed horizontal telescope with a 40-foot focal length that would direct sunlight to a heliostat (“a slowly turning mirror that kept the Sun’s image stationary with respect to the telescope”).11 The lens and heliostat mirror would be mounted on a four-foot iron pier embedded in concrete (imagine traveling with that!). The lens would create an image that was four inched in diameter and projected onto a photographic plate placed 38.5 feet away on another concrete mount.12 Compared to the solar eclipse coming up on April 8, 2024, which will last 2.5 hours with only four minutes and twenty-eight seconds of totality, the 1874 transit of Venus was anticipated to last close to four hours.13 Still, that is a small window of time for the work astronomers were hoping to complete.

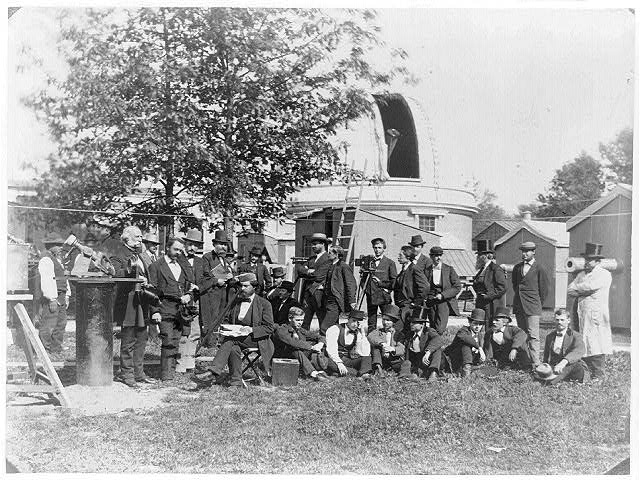

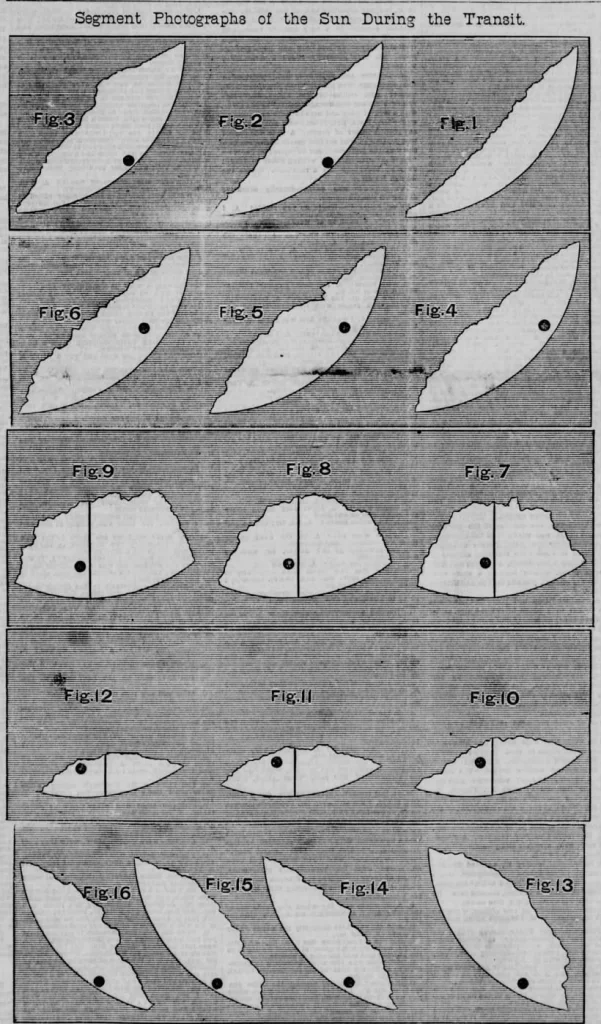

On March 3, 1871, Congress approved a $2,000 expenditure for “preparing instruments” for an expedition.14 Superintendent of the U.S. Naval Observatory, Commodore B.F. Sands, petitioned Congress for an additional $150,000, stating that the transit of Venus was “one of the rarest and most interesting phenomena in astronomy” and an expedition for its observation “will afford our countrymen a peculiarly favorable opportunity to exercise their inventive ingenuity in the introduction of improved modes of observation.”15 In total, $177,000 was invested in the 1874 expedition, which included eight separate teams of astronomers and photographers.16 Not a single one of these groups was actually stationed on the continental United States – three teams were sent to Asia, four to Australia, and one to Antarctica. Otto Struve, an astronomer with the Russian Academy, wrote to Simon Newcomb in the United States in February 1873, recommending “the coast region [by] Wladivostok [sic] should be chosen as principal station on the part of the Americans.”17 Of the eight teams, there was no specified “principal expedition, but the Kansas City Weekly places the Valdivostock team including T.S. Tappan at the top of their list when reporting on the expeditions and the New York Daily Herald dedicated an entire page to this group and their work, giving special credence to the Siberian station.18 Headed by Professor Asaph Hall of the United States Navy, Tappan was appointed as the assistant photographer, bringing the desired skills of a “young gentleman of education . . . who had been practiced in chemical and photographic manipulation.”19 The group set sail for Vladivostock in July 1874, a journey that took a little over a month, to await the main event of December 9, 1874.20 Unfortunately, poor weather on the day of the transit meant the group only secured thirteen photographs but those were good enough to be fully reproduced in the New York Daily Herald in February 1875.21 When Tappan was called upon to photograph the transit of Venus again in 1882, he and principal photographer of the New Mexico expedition, D.C. Chapman, produced the highest volume of usable photographs of any expedition group that year, with a total of 216.22

According to the Directory of Indiana Photographers, Thomas Shaw Tappan was born in Cincinnati, Hamilton County, Ohio on October 28, 1838, the youngest son of Benjamin Tappan and Elizabeth Shaw.23 It is said that Tappan “developed a remarkable reputation as a photographer in Cincinnati, then Wheeling [West Virginia]” and the Directory of Indiana Photographers lists him as owning three studios in Noblesville, Hamilton County, Indiana between 1861 and 1866.24 IRS tax assessments from 1863-1865 confirm Tappan was working as a photographer in Noblesville.25 The spelling of Tappan’s surname is inconsistent in these tax assessments and his various photography studios and businesses were commonly listed under “Tappin,” which makes a thorough record of his work and whereabouts difficult to produce with absolute certainty of its accuracy. In the summer of 1863, twenty-four-year-old Tappan’s name appears in a draft record for the U.S. Civil War.26 Family histories like Jay Tappan Gilbert’s 1969 book do not mention anything about Tappan serving in the war but Gilbert suggests that it was likely around this time that Tappan “became associated with Mr. Leon Van Loo,” a photographer and artist most famous for introducing the “ideal” style of photography in which images “were printed on zinc oxide and applied to blackened sheet-iron.”27 What had prompted Tappan’s move to Noblesville is uncertain but by 1873, he was once again in Cincinnati, being found in the city’s directory listed as an artist.28 Newspapers and other records of the time offer scant commentary on Tappan’s artistic credentials, but it would seem an association with the famous Van Loo could only have drawn interest to Tappan when the Venus expeditions were being planned. Tappan’s relationship with Van Loo was evidently so influential and important to him that he named his youngest son Leon Van Loo Tappan.29

Tappan wrote many letters during his time away from home in 1874 and the Sherman Room has a small collection of those letters in our collection. He appears to have developed a particular fascination with Japan where his group had briefly stayed before making the final leg of their journey to Vladivostock. According to The Cincinnati Daily Star, Tappan “found in Japan a Cincinnatian, who has established himself very successfully at Sepparo, Island of Yesso, in the manufacture of flour.”30 Even a decade later, and after observing another transit of Venus, Japan was still on Tappan’s mind when he was invited to give a lecture to the Columbia Club in Wheeling, West Virginia. He told those in attendance about “the country, its people, their manners and customs, their religion, etc.”31 He concluded his talk with a display of Japanese fireworks he had acquired on the trip (one can only hope the presentation was outdoors).32

By the time Tappan was called upon again to capture the transit of Venus in 1882, he and his family had relocated to Wheeling, West Virginia. The family is shown in Bellaire, Ohio in an 1880 census, but by the next year, The Dail Register of Wheeling was proudly proclaiming Tappan “our photographer.”33 With only five miles between the two cities, Tappan may have maintained businesses in both cities, and he gave each city a boost of notoriety when he left for New Mexico in 1882. He first traveled to Washington, D.C. to join the rest of the expedition but he showed particular excitement for what he might find out West. The Wheeling Daily Intelligencer reports he took a rifle with him should he encounter and prime buffalo, deer, or other such game.34 For his efforts and photographic expertise in New Mexico, Tappan would be paid “three dollars a day and five dollars for subsistence and all other personal expenses.”35 He was once again an assistant photographer on the expedition but the Las Cruces Sun-News in New Mexico notes he had the foresight to document to occasion for posterity, writing, “the assistant Photographer, Mr. T.S. Tappan, of Bellaire [?], arranged the whole party in a group with the queer-looking buildings and the whole country for a background, and there photographed us. It was a noble group (our majestic figure in near the centre [sic]) and represented Science supported by Literature, and protected by Military Force.”36 Though Tappan promised to furnish the paper with a print of the photo, no extant copy has been located to prove he kept his word.

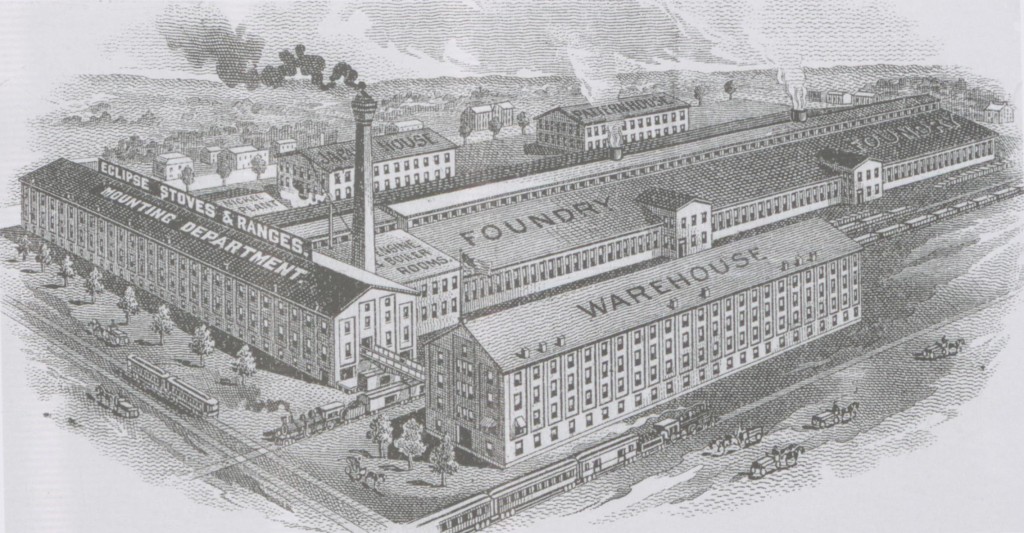

Tappan married Mary Elizabeth Steward [Stuart] on December 7, 1858.37 Together, they had four children: William Jared (1860-1936), Thomas S. (1865-1945), Katie Lavonda (1872-1902), and Leon Van Loo (1879-1939).38 In 1881, William Jared, along with J.M. Maring and W.A. Gorby, purchased the Ohio Valley Foundry Company in Bellaire, Ohio. This company, specializing in the manufacture of cast iron stoves, was the earliest precursor to the Tappan Stove Company.39 After a devastating fire in 1889, the company relocated to Mansfield and The Evening News in Mansfield announced the company had” been granted a new charter under the new name of Eclipse Stove Company by which it will hereafter be known.”40 Eclipse Stove Company was incorporated in 1918 but William Jared and his business partners soon discovered there was another Eclipse Stove Company operating out of Illinois. In a mutual decision, both companies decided to change their names and in 1921, William Jared’s company was rebranded one final time as the Tappan Stove Company.41 Thomas Shaw Tappan had little, if any, direct involvement with his son’s stove company, but when he passed away in October 1906, the shops of the Eclipse Stove Company were closed for his funeral.42 Whether inspiring the branding of kitchenware or the work of astronomers of the twenty-first century and beyond, Thomas Shaw Tappan’s eclipse legacy is one that won’t soon be forgotten.

- Paul L. White, “This is the Mansfield That Was,” News Journal, May 15, 1966, 5. ↩︎

- “The Transits of Venus in 1874 and 1882,” Scientific American Magazine 20, No. 18(May 1869), 281. ↩︎

- The Mansfield News, November 19, 1899, 9. Emphasis added. ↩︎

- Michael E. Bakich, “What are Solar Eclipses and How Often Do They Occur,” Astronomy, March 20, 2024, https://www.astronomy.com/observing/how-often-do-solar-eclipses-occur/; Steven J. Dick, Sky and Ocean Joined: The U.S. Naval Observatory, 1830-2000 (Cambridge, U.K. and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003): 241. ↩︎

- William Harkness, “Address by William Harkness,” Proceedings of the AAAS 31st Meeting . . . August 1882 (Salem, 1883), 77 as quoted in Dick, Sky and Ocean Joined, 238. ↩︎

- “Transit of Venus,” Wikipedia, March 14, 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transit_of_Venus. ↩︎

- Harkness, “Address by William Harkness.” ↩︎

- Dick, Sky and Ocean Joined, 238. ↩︎

- Dick, Sky and Ocean Joined, 243. ↩︎

- Dick, Sky and Ocean Joined, 245. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Dick, Sky and Ocean Joined, 245-246. ↩︎

- NBC Chicago Staff, “How Long Will April’s Solar Eclipse Last? It Depends on Where You’re Located,” 5 Chicago, March 24, 2024, https://www.nbcchicago.com/solar-eclipse-illinois-2024/how-long-will-aprils-solar-eclipse-last-it-depends-on-where-youre-located/3391935/; “1874 Transit of Venus,” Wikipedia, February 7, 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1874_transit_of_Venus#cite_note-2. ↩︎

- Dick, Sky and Ocean Joined, 244. ↩︎

- Dick, Sky and Ocean Joined, 247. ↩︎

- According to data from Steven J. Dick, a minimum of $34,000 was spent to supply all 8 teams with the same specialized equipment. See Dick, Sky and Ocean Joined, 248. ↩︎

- Dick, Sky and Ocean Joined, 253, n.19. ↩︎

- “Venus,” Kansas City Journal, December 6, 1882, 5; “Transit of Venus,” New York Daily Herald, February 17, 1875, 3. ↩︎

- Dick, Sky and Ocean Joined, 253. ↩︎

- According to a letter dated September 14, 1874, the total journey from Ohio to Vladivostok took 56 days. See Jay Tappan Gilbert, Tappan Family History (Mansfield, OH, 1969): 27. ↩︎

- Dick, Sky and Ocean Joined, 259; “Transit of Venus,” New York Daily Herald, February 17, 1875. As of 2003, it is reported that none of the photographs from the 1874 transit expeditions survived. See Dick, Sky and Ocean Joined, 261. ↩︎

- Dick, Sky and Ocean Joined, 267. ↩︎

- “Tappin, Thomas Shaw, Sr.,” in Joan E. Hostetler, Directory of Indiana Photographers (Indianapolis, IN: The Indiana Album, Inc., 2021),np, https://indianaalbum.com/photographers/data/PersonData1-CATNUM-322.html; Jay Tappan Gilbert, Tappan Family History (Mansfield, OH, 1969): 10. ↩︎

- Hostetler, Directory of Indiana Photographers. ↩︎

- “U.S., IRS Tax Assessment Lists, 1962-1918 for Thomas S Tappan,” Indiana – District 11; Annual Lists; 1863. Available through Ancestry.com; “U.S., IRS Tax Assessment Lists, 1962-1918 for Thos S Tappin,” Indiana – District 11; Monthly Lists; Jan-July 1864. Available through Ancestry.com; “U.S., IRS Tax Assessment Lists, 1862-1918 for Thos S Tappen,” Indiana – District 11; Annual Lists; 1865. Available through Ancestry.com. ↩︎

- “U.S., Civil War Draft Registrations Records, 1863-1865 for Thomas S Tappin,” Indiana – 11th – Class 1, T-Z, Volume 3 of 6. Available through Ancestry.com. ↩︎

- Gilbert, Tappan Family History, 25; Alexandra Daniels, “Leon Van Loo: A Man of Many Talents,” Special Collections and University Archives, NKU, December 5, 2013, https://nkuarchives.wordpress.com/2013/12/05/leon-van-loo-a-man-of-many-talents/. ↩︎

- Williams’ Cincinnati Directory for 1872-73, 817. Available on Ancestry.com. ↩︎

- See Gilbert, Tappan Family History, 10; “U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918 for Leon Vanloo Tappan,” Ohio – Richland County – All – Draft Card T. Available on Ancestry.com. ↩︎

- The Cincinnati Daily Star, March 5, 1875, 4. ↩︎

- “An Interesting Lecture,” Wheeling Sunday Register, November 29, 1885, 3. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- “1880 United States Federal Census for Thomas Tappan,” Ohio – Belmont – Bellaire – 026. Available on Ancestry.com; The Daily Register [Wheeling, W.V.], April 8, 1881, 4. ↩︎

- The Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, November 4, 1882, 4. ↩︎

- Gilbert, Tappan Family History, 27. ↩︎

- “Transit of Venus,” Las Cruces Sun-News [Las Cruces, NM], December 9, 1992, 3. ↩︎

- “Ohio, U.S., County Marriage Records, 1774-1993 for Thomas S. Tappin,” Hamilton – 1858-1860. Available on Ancestry.com. ↩︎

- Gilbert, Tappan Family History, 10. ↩︎

- Richard D. Witchey Jr. interview with P. R. Tappan, retired Chairman of the Board of Directors of the Tappan Company, May 22, 1964. See Richard D. Witchey Jr., “Industrial Growth of An Enterprise: A Study of the Tappan Company,” Master’s Thesis (Kent State University, 1966), 5. ↩︎

- “The City in Brief,” The Evening News [Mansfield, OH], January 20, 1891, 4. ↩︎

- Witchey Jr., “Industrial Growth of an Enterprise,”20. ↩︎

- “Closed for Funeral,” The Mansfield News, October 29, 1902, 6. ↩︎